Wax, Fire, and Light: an Interview with Doki Kim

The South Korean artist's dynamic, temporal sculptures melt, smoke, and glitch. In an interview via a translator, we discuss her interest in thermodynamics, transformation, gender fluidity, and more.

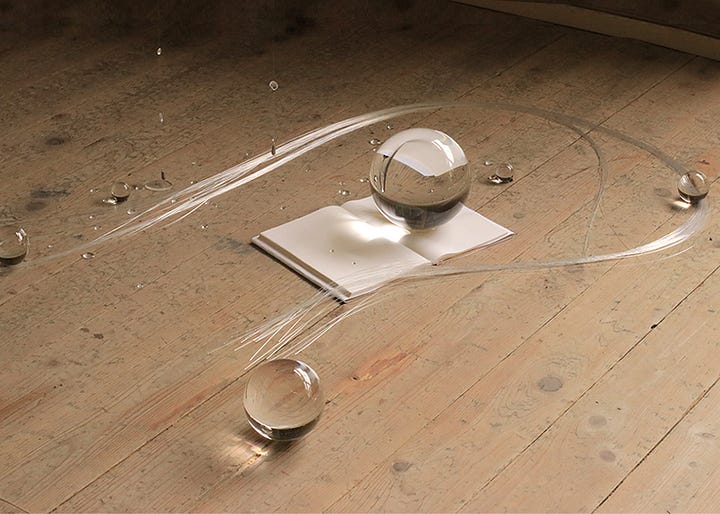

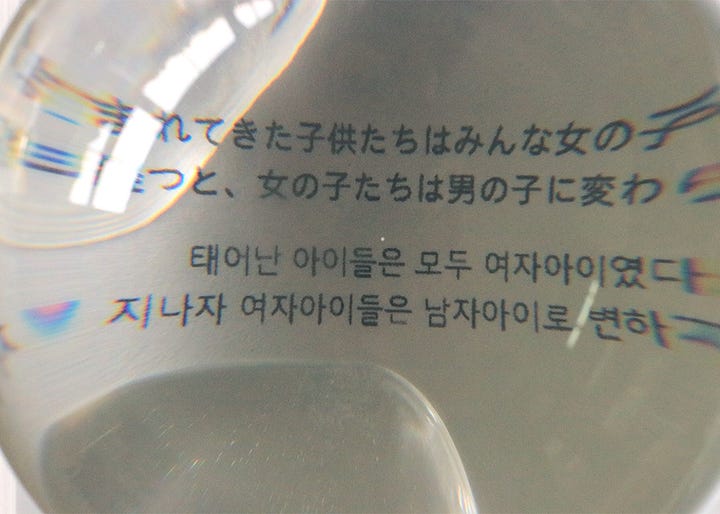

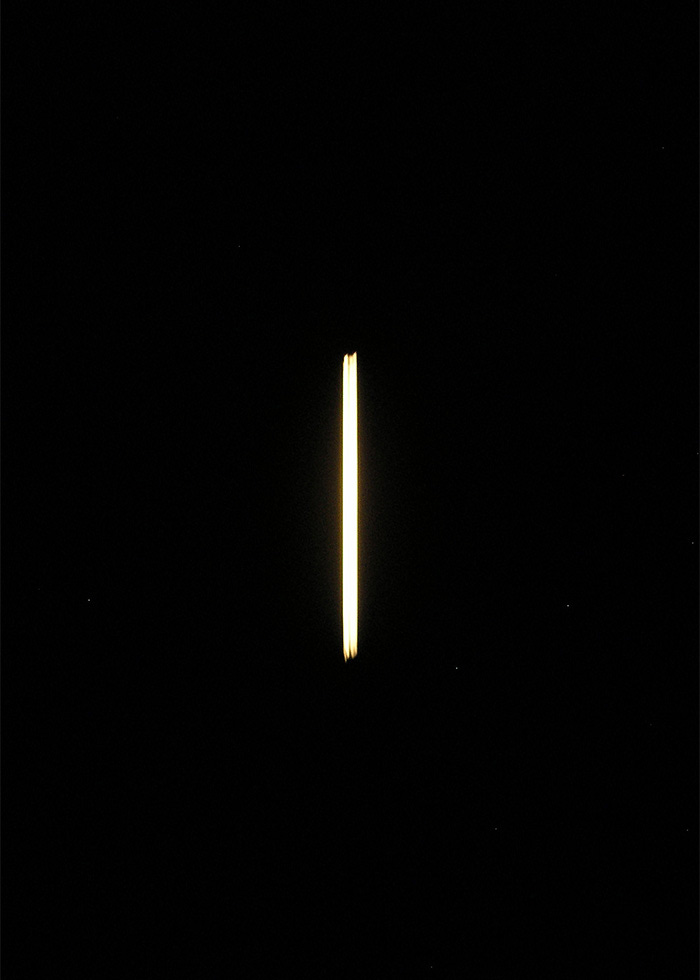

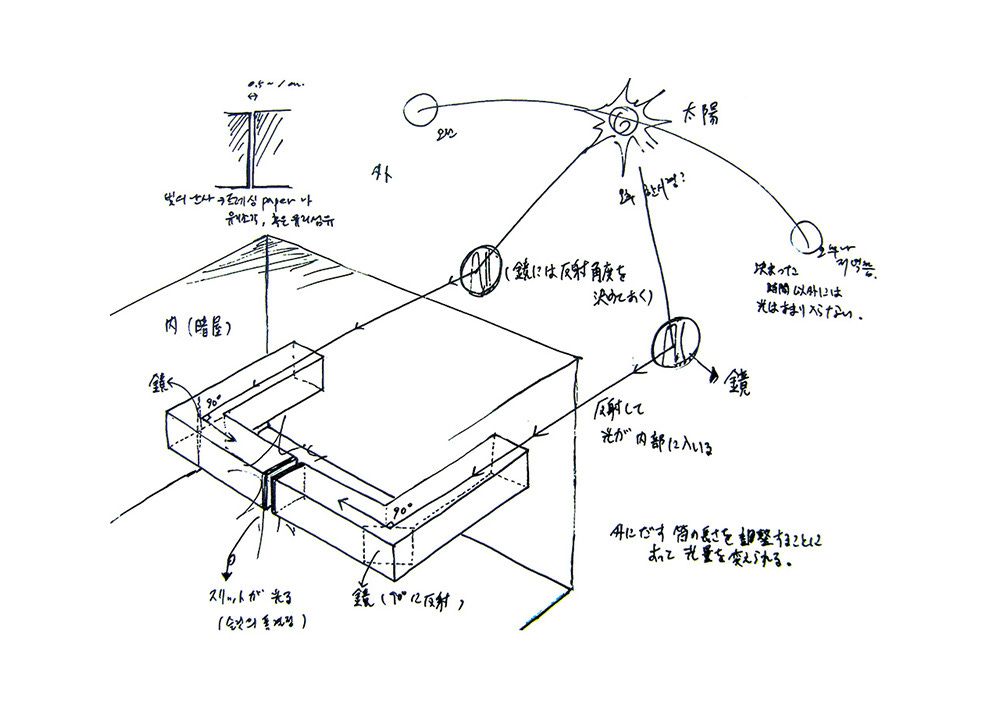

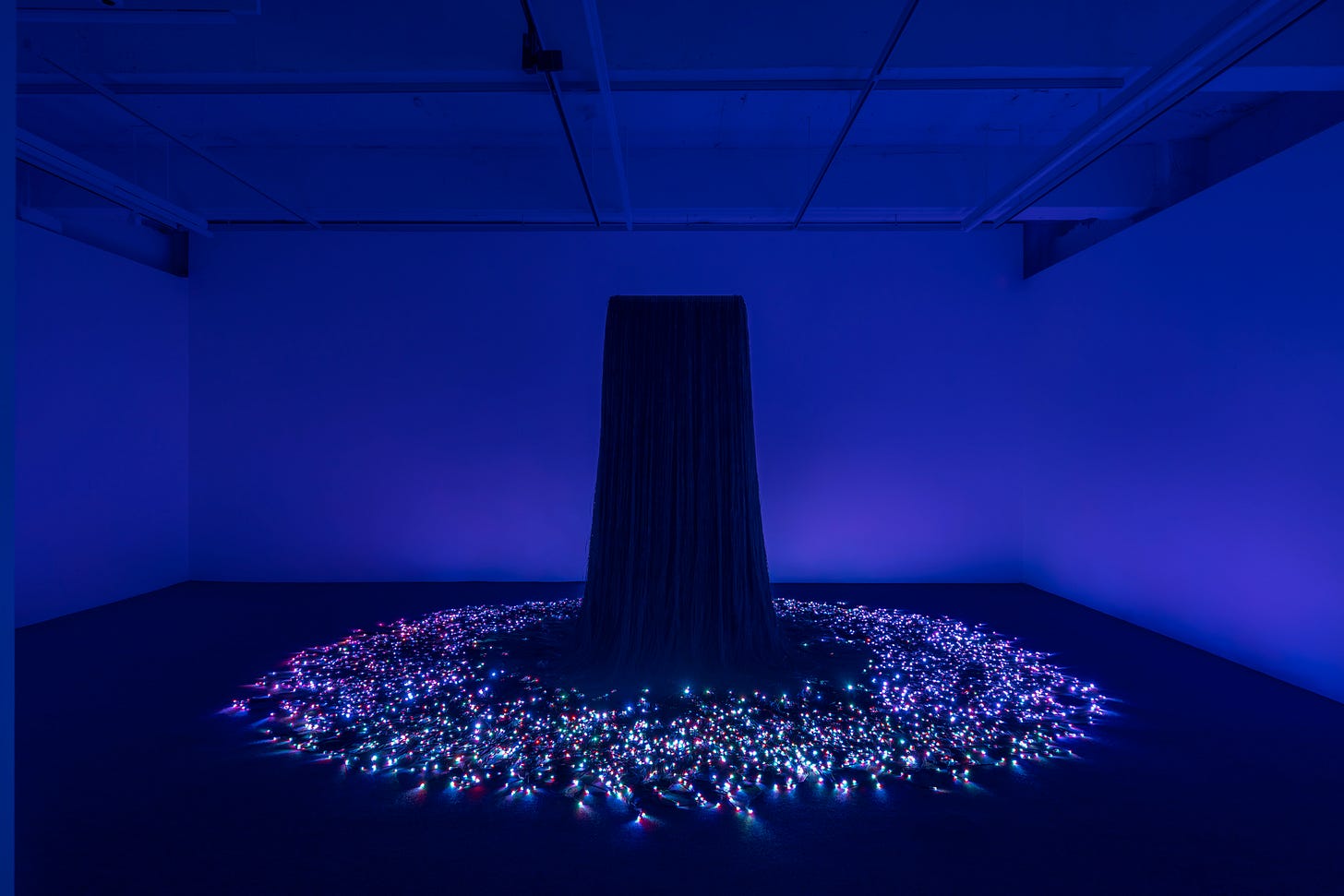

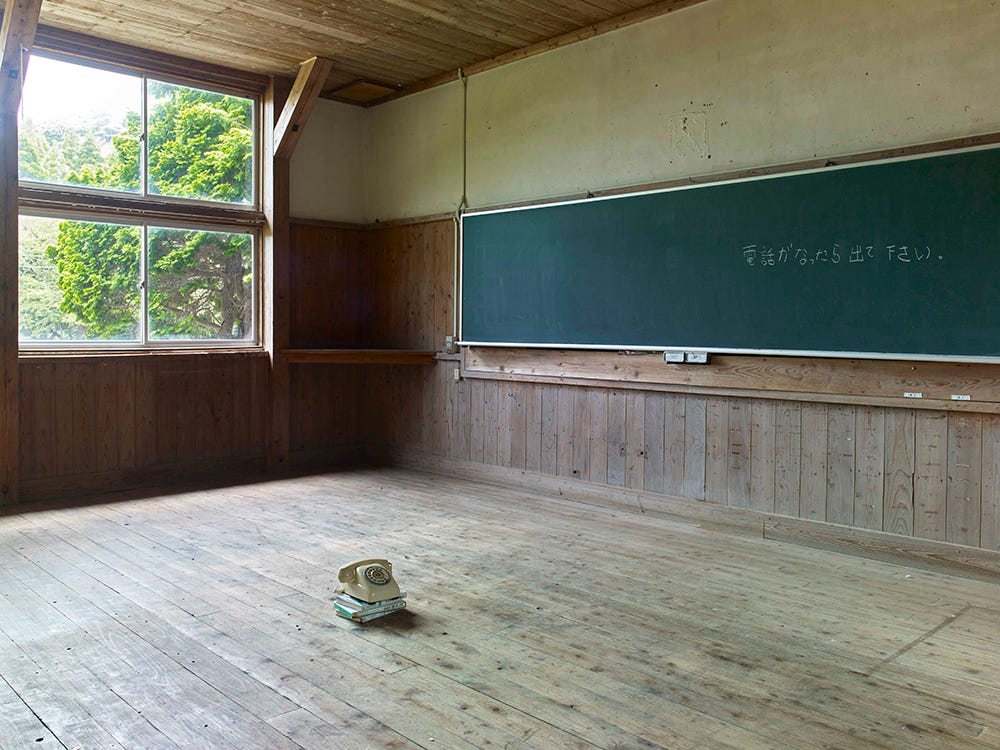

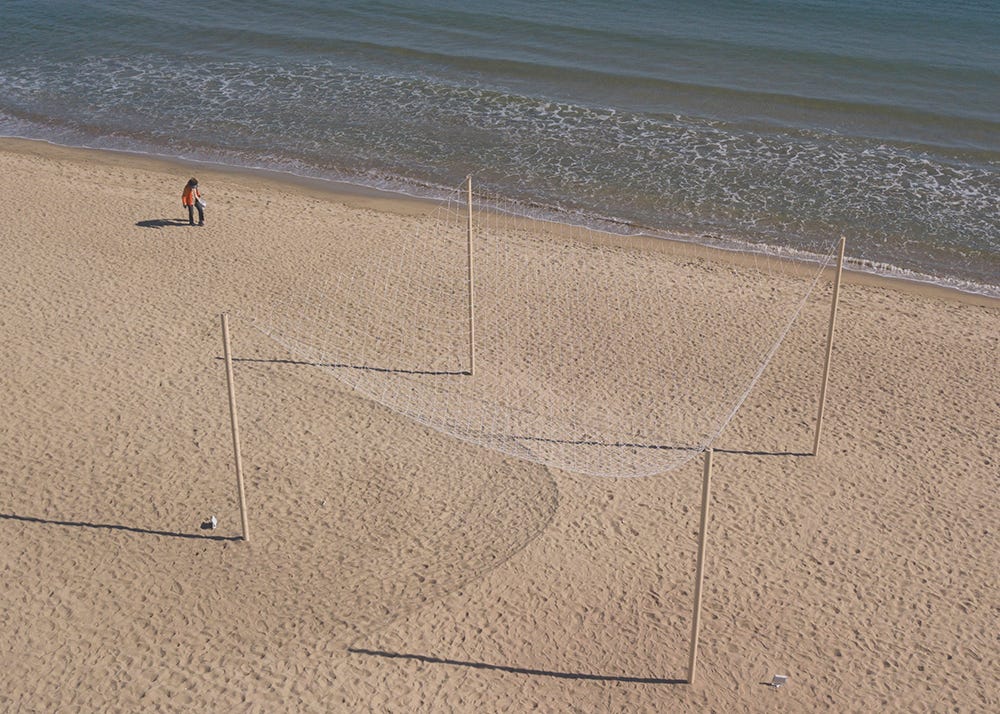

To encounter a Doki Kim installation is to get hit in the head with Einstein’s proverbial apple and undergo an act of discovery that leads to a shift of perception. Sit with a work long enough and new forms will materialize from shadows and light. Kim’s recurring materials include heaters (turned on), paraffin wax, stainless steel, and LED lights, which push up against each other in compelling ways. Think rooms filled with wax with a single flickering flame, a heater embedded in a bed frame, a phone in an empty room that the artist calls, water-absorbent beads, translucent mountains that project animals onto ceilings, slits in dark rooms for light to shine through, and glass orbs that magnify texts on gender fluidity in nature.

While visuals of the artist’s large-scale installations keep a static record of works in flux, the objects themselves are animated: breathing, sparkling, steaming, melting, twitching under her deft hand. Each installation beckons a closer look and begs an in-person view. For an American like myself, there is an elusive quality to writing about Kim with only images and videos for reference—the 44-year-old artist lives and works in Busan, Korea and has only exhibited in her home country and Japan. I wrote about Kim’s recent exhibition at Gallery Baton for Family Style (read here for a more comprehensive overview of her practice). But it wasn’t enough to look at the work, I wanted to hear from Kim herself. What follows is a conversation between Kim and I, translated by MG Im from Gallery Baton.

What is your first memory creating art?

Officially, the first artwork I ever made was probably one of several I made in college. However, unofficially, I'd say it was an act of mourning when I hid a single chrysanthemum flower from the adults while cooking holiday food on a briquette brazier and then plucked the petals off and burned them in the brazier. It was a very intense memory, and that feeling still survives and influences my work.

What is the first artwork you saw that moved you?

Face of Jiwon by sculptor Kwon Jin-kyu. I learned about it through an art textbook when I was in middle school. I tore its picture out of the textbook and carry it with me daily. I can't fully express the depth of his work in any words. There is a resonance there that goes beyond language.

Do you have an unrealized project?

Sometimes, as a piece of art grows in size, it can communicate on a different level. Most of my works are small because my studio is also small. However, I hope to create a large-scale installation in a spacious, high-floor area using pixels, paraffin, or heat at some point in the future.

Can you explain your interest in thermodynamics?

When I look at the torn fabric, I feel no regret but rather astonishment that I can never return to the beginning again. Rather than being sad that the tiny snowflake that lands on my hand quickly melts, I wonder if the same forces that apply equally to all things in this vast universe have fallen upon my hand. If I pay attention, a galaxy hundreds of millions of light years away is as familiar as if it were right next to me because we all follow the same principle.

How does site specificity influence your installations?

Adapting the artwork to the various elements of the site where it will be installed is necessary at all times. I think the most important part of an art installation is that the space and the artwork work well together so that the viewer is fully immersed when they enter the space. Hence, the unique characteristics of a location, such as the roughened textures of an old site and the clean surfaces of a white cube, necessitate a completely different approach to understanding the site and the artwork. Even if the same artwork is displayed in both settings.

In To Night, From Night, what does the concept of night mean to you?

I often use the metaphor of a supernova explosion to describe the meaning of ‘night’ in my work. Just as the stellar debris and dust from a supernova becomes the source of new stars, the ‘night’ in my work is a world that is unpredictable, chaotic, and nonlinear, but teeming with “possibilities” for something new to be born. This ‘night’ can also be seen as a world of death, though it's important to note that death leads to rebirth. These flexible, dynamic, but chaotic and chaos-filled worlds often lean towards the non-established, the non-mainstream, the marginalized, and the weak. The two giant paraffin mountains in <To Night, From Night> could be described as 'night personified'. The fragile hands reaching out towards each other through the thick coat of night are like the tiny lights in <The Melting Sun in the Night>(2021), symbolizing the power of possibility, initiation, and solidarity.

In Umbra , where did you source the LED lights, and what is the original image of the video that is deconstructed? + Q14. What is the video that is fragmented in Umbra? And is there a sound element?

I began working on the Pixel series in 2018. My inspiration came from the signs I regularly saw on the high street as I commuted home from work. The light from the bulbs surrounding the signs seemed to move in a circular motion, but if you focused on just one bulb, you could see that the light only flickers on and off. Observing this, I started to ponder whether our perception of time is similar to this phenomenon. Perhaps time is merely an illusion created by our senses, rather than a tangible flow. This idea led me to consider the parallels between the minimal units called pixels in a display and the real world. I then decided to break down each pixel in an LED display in order to delve into the temporal and narrative aspects of the world we perceive.

The videos in <Umbra> showcase everyday stories such as children running races, celebrating the New Year in different countries, cooking, and singing. Additionally, various events from around the world, such as natural disasters like lightning strikes and forest fires, as well as scenes from wars and games, are continuously played. <Umbra> is a three-dimensional work that can be viewed from all angles, providing a 360-degree experience. There are four displays assembled on the left, right, front, and back sides, and the sound from each video is played simultaneously on all four displays. Upon entering the gallery space, various sounds resonate loudly and sometimes quietly, creating an environment that seems to reflect the earth.

Can you explain the technology and process behind your pixel works?

The Pixel series utilizes commercial, low-resolution LED displays, which are not typically used in homes. The LED display consists of a PCB board with light-emitting diodes and a control card to transmit the image. The process is quite simple. For <Umbra>, <Blue Hour>, and <Quantum Dream>, I use wires instead of showing images by aligned pixels. So, people see only RGB colors that have been transformed from the original images.

Do you consider the physical act of making and installing your works a performance?

To me, the process of creating and installing artwork is more like the intense life of wild animals in the savannah rather than a performance in the art world. You are always on your toes, timing your attacks and defenses and solving the many problems that arise. It feels like constantly alert and strategic, similar to a cheetah stalking its prey or a wildebeest cub encountering a lion. At times, I even consider the courage (or foolishness) of a zebra biting the neck of a crocodile.

How does your practice engage with transformation?

Transformation is basically a motion and a state. It is the most fundamental physical phenomenon in the universe. Rocks, earth, stars, ants, humans, and nameless roadside grasses are constantly moving and changing in their own time, but according to the same principle. This state of change and transformation is the most natural for me, the basis of my work, and the form of life I want to pursue.

As an artist working with media and materials that change over the duration of the installations, when is a work finished?

There is no such thing as completion, especially when working with materials that change their properties. It is not easy to find the optimal conditions for change, set up the work, and control all the many variables that occur during the material change process. However, this is the best part of using immaterial materials that change their properties during the installation process as a working medium.

You have made works in the past that require interaction with the viewer, such as a phone that you called twice a day and a book that could be read through a glass orb; other times your works flicker or steam or emit sound. What is the role of the audience?

A lot of my work is based on interacting with the viewer. Without interaction, the work is meaningless. It only becomes a complete work when the viewer discovers and experiences it.

What is the significance of the Former Tsushima City Kuta Elementary School Branch in your practice? I see you have done multiple installations in its rooms over recent years.

I loved the years I spent working on the island. It was an exceptional experience. The Kuta Elementary School branch was a small, beautiful wooden building that had been abandoned, but there were still photos and records of students all over the building. It wasn't just an abandoned building; it felt very much alive on the island, like an old tree hundreds of years old. The school's architecture, the environmental uniqueness of the Naiin area, and the relationship between the local people and the architecture made it feel like a work of art in itself. This experience inspired me to develop the work that followed.

Can you speak more about the children that Children of the Sea is referring to? How can understanding the gender fluidity of natural organisms help acceptance and understanding of transgender identity in humans?

Albert Einstein said “A human being is a part of the whole called by us universe, a part limited in time and space.” He experiences himself, his thoughts and feeling as something separated from the rest, a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty]. When humans over-categorize and generalize, prejudice builds up, leading to discrimination and hatred. Understanding gender fluidity in natural life is like widening the circle of empathy, an idea often associated with Einstein. Recognizing that we are not fundamentally different from our fishy ancestors goes beyond accepting sexual diversity; it is also linked to addressing racism, nationalism, discrimination, and attacks on animals.

lovely ofc